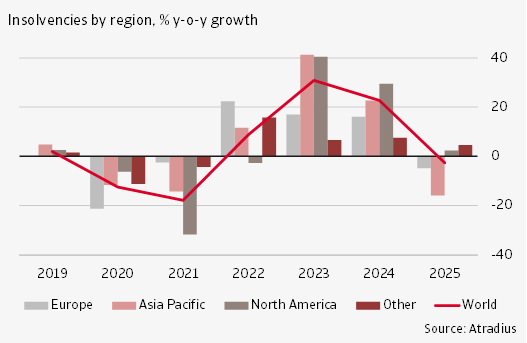

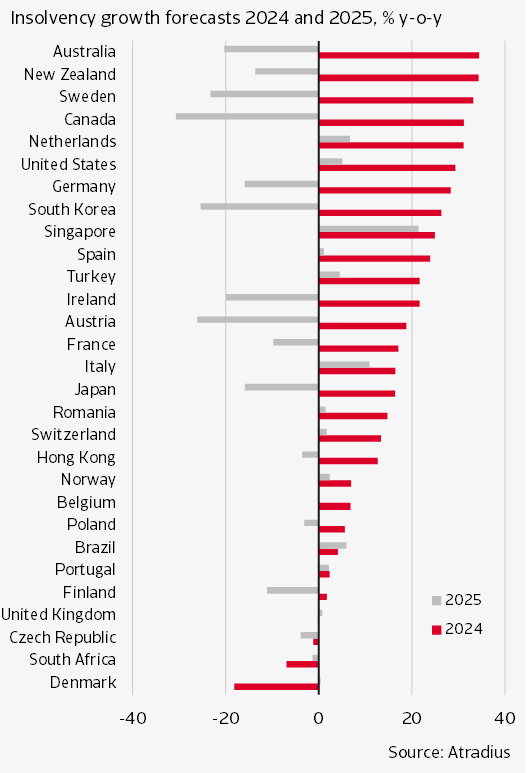

Global insolvencies are expected to increase by 23% in 2024, followed by a minor decline in 2025. For the majority of countries, insolvencies are increasing this year. This is partly a post-pandemic adjustment driven by the loss of large-scale government support. Another reason, however, is the weak economic environment in combination with tightened credit conditions. Cash reserves built up by firms after the pandemic are now under pressure due to shrinking profit margins and tighter funding conditions. The increased debt burden, accumulated during the pandemic, is becoming harder to service in an environment with higher interest rates and lower growth.

In a number of markets insolvencies already reached a level above normality. In some markets, like the UK and Switzerland, insolvencies are stabilising at an adverse new normal, while in other markets, like Austria, Canada and Sweden, there is a temporary spike in insolvencies in 2024.

The global economy is expected to show a moderate expansion of 2.7% this year. While GDP growth is steady, it remains low by historical standards as past monetary tightening weighs on demand. Despite a relatively slow start to the year, the US economic outlook for 2024 remains positive. The risks in the US economy seem finely balanced and a gradual slowdown through the rest of the year is the most likely scenario.

In the eurozone, growth is expected to remain sluggish this year. Countries in Southern Europe, such as Spain, Portugal and Greece, are doing relatively well, due to a growing tourism sector, recovery in the labour market, and fiscal support as part of the NextGenerationEU plans. Germany remains a weak spot due to its sluggish manufacturing sector. The growth picture in 2025 is looking slightly better for the eurozone as a more benign inflationary environment supports consumers’ purchasing power.

Bank lending surveys in both the US and eurozone still show a further tightening of lending standards for companies in the coming months. Eurozone banks reported a small further tightening of credit standards in Q2 of 2024. Similarly, US banks also modestly tightened standards on company loans in the second quarter. Both eurozone and the US banks cite a more uncertain economic outlook as the main reason behind the tightening of funding standards. Together with squeezed profit margins this is weighing on firms’ cash buffers and leads them to operate in a more challenging economic environment.

Insolvencies continued to climb up in most markets

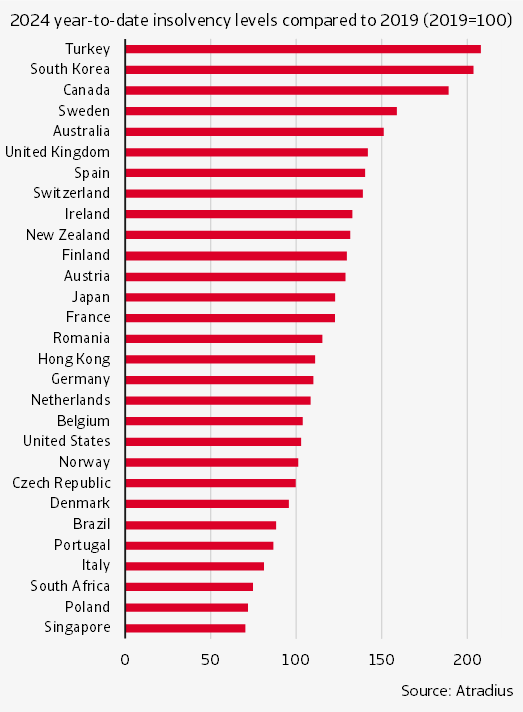

Globally insolvencies increased by 31% year-on-year in 2023 and they continued to increase in the first half of 2024. Out of the 29 markets that we monitor in this report, 23 have adjusted fully back to normal or are even overshooting the pre-pandemic insolvency levels. We consider a market as having fully adjusted back to normal if the insolvency level is at least 95% of the 2019 level. Therefore, at this moment only in a minority of markets the adjustment back to normal is still underway.

Figure 1 gives the year-to-date insolvencies index in 2024. A value above 100 indicates that the insolvency level is above the (pre-pandemic) 2019 level. A value below 100 means that the insolvency level is still lower than in 2019.

Countries like Turkey, South Korea, Canada, Sweden, and Australia have relatively high insolvency levels in 2024 compared to 2019. While each country faces unique economic challenges, some common factors contribute to the trend. In Turkey, the economy is slowing considerably in 2024 as the government has started to increase taxes and interest rates and is limiting access to credit. The growth slowdown and still-high interest rates is creating a challenging environment for the debt-burdened private sector to operate in. For South Korea, high corporate debt in combination with higher interest rates is weighing on the business environment. In Canada, companies are facing several challenges such as having to repay government loans taken out during Covid, high input costs and high labour costs. In Sweden, high insolvencies are attributed to the economic recession, high interest rates and high costs. A similar picture arises in Australia: weak consumer spending and high input costs squeeze companies’ profit margins, driving up insolvencies. Another factor that is contributing to Australian insolvencies is that the Australian Taxation Office is pursuing debts that were previously put on hold during the Covid pandemic.

Countries with low insolvency levels compared to pre-pandemic include Singapore, Poland, South Africa, Italy, and Portugal. Generous government support during the Covid pandemic played its role here, such as in Italy and Singapore. This helped firms strengthen their liquidity and cash reserves, preventing a sharp rise in insolvencies after the support was withdrawn. In the case of Italy and Poland, the low insolvency levels are also partly attributed to new regulations that facilitate out-of-court company restructurings.